Friday August 16, 2001 11:39 AM

ROME (Reuters) - If you end up in purgatory after you die, never fear. Just remember to send a message to those surviving you, care of a riverside church in Rome. The Church of the Sacred Heart houses one of the world's most unusual and smallest museums -- a collection of signs sent from beyond the grave by souls stranded in purgatory.

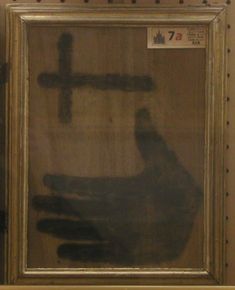

Scorched fingerprints on prayer books, handprints burnt on to wooden tables, and singed pillowcases and shirt sleeves seem to be the purgatory equivalent of paper and pen. "Most of our visitors are motivated by curiosity. But faith is the key to understanding the relics," Roberto Zambolin, the church's priest-cum-tour-guide, told Reuters on Friday.

Catholics believe spirits, stuck between heaven and hell until they have atoned for their sins, can hasten their entry to paradise if family and friends on earth pray for them. And some purgatory residents obviously felt their loved ones needed a gentle reminder. Branding an imprint of his left hand on to a light-brown wooden table was one 18th-century friar's way of reminding colleagues to say more masses and speed his soul to heaven, Zambolin says. On a single day in 1731, the deceased Friar Panzini not only marked the table, but burnt a handprint on to paper and twice clutched at the sleeves of a nun's tunic, leaving scorch marks.

Panzini's spiritual smoke signals are a taster of what's on display in a bare room, dubbed the Little Purgatory Museum, off to the side of the church. While most tourists to Rome flock to the Coliseum or the Vatican, some stray off the beaten track to the quiet and unassuming museum to ponder the mysterious relics, gathered from all over Western Europe. "I'd say we get about 4,000 visitors a year -- young, old, Italians, foreigners, believers, non-believers," Zambolin said.

Peering at four fiery fingerprints emblazoned on a prayer book, Austrian students Michael Weisskof and Karl-Heinz Larcher debated the validity of the relics."I believed in purgatory before, but seeing these relics reinforces my faith," 25-year-old Larcher said. But his 19-year-old friend was more hesitant.

"I'm not sure what I think. They are certainly spooky but even if it's not true, it's a good story," Weisskof said.

The museum, about 100 years old, was the brainchild of Victor Jouet, a French priest who travelled to Belgium, France, Germany and Italy, scooping up relics to display in his gothic church on the banks of the Tiber.

Jouet died in the museum's only room in 1912, surrounded by his treasures, but the collection lives on despite a discussion in the late 1990s about whether to close it. "We realised that most visitors were not Christians but those interested in the paranormal, or in some cases the devil," Zambolin said.

"The Church didn't want to encourage something that wasn't to do with faith. But in the end the decision was made to keep it open. The collection does start discussions about Catholic ideas," he added. And although most of the fiery signals date back to the 19th century or earlier, Zambolin doesn't think the lack of modern-day signs has any significance.

"We don't get any new objects sent to us, but we don't need new signals to believe in purgatory today."

RSS Feed

RSS Feed